Why the Next Stats4PT Lesson Is Taking Longer Than Usual

— a brief update for Clinical Inquiry Fellows

The upcoming Stats4PT lesson—“Beyond Data: Mechanisms and Structures in Evidence”—is taking longer than I expected. Not because of writer’s block, but because I find myself at the crossroads of two foundational tensions that sit at the heart of causal reasoning in clinical practice.

1. The General vs. the Particular

In statistics, we distinguish between standard deviation (variation within a population) and standard error (the precision of an estimate about that population). This difference reflects a deeper tension in clinical reasoning:

Are we identifying a cause that generally contributes to an outcome?

Or are we identifying what caused this specific outcome in this specific case?

This distinction is subtle but essential. When we say, “manual therapy reduces pain,” do we mean on average, across populations? Or do we mean it did so for this patient? These are not interchangeable claims. They require different kinds of evidence, different ways of thinking about mechanisms, and different forms of inference.

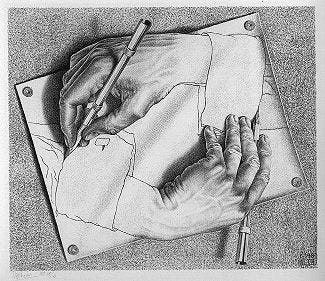

In practice, these two directions of reasoning are recursively entangled. We build an understanding of general causal relationships by observing many particular cases (induction), and then we interpret the particulars of a case in light of that general knowledge (deduction). When a patient asks, “Did X cause me to feel Y?”—they’re asking a particular question. But our ability to answer depends on what we believe about general relationships and, crucially, about mechanisms.

If we lack prior experience or general knowledge about whether X could cause Y, we turn to mechanistic reasoning: Is there a plausible process by which X leads to Y, is that process coherent with our worldview? This mechanism is, itself, a general belief—whether learned through experience, study, or structured inquiry. (I’ve been digging deeper into this lately through Kolb’s Experiential Learning, Piaget’s work on knowledge construction, and Causal Learning, edited by Gopnik and Schulz all within what our silo’s would consider psychology. The convergence is clear: we learn about causes in multiple ways, but all hinge on the recursive flow between particulars and generalizations.)

2. The Objective vs. the Situated Knower

The second tension is epistemological. Following thinkers like Jean Piaget and Michael Polanyi, I’ve been reflecting on the relationship between objective knowledge and the subjective process of knowing.

Piaget argued that epistemology can’t be separated from psychology—our ways of knowing are inherently shaped by our cognitive development and learning. Polanyi famously said, “We know more than we can tell,” emphasizing that personal commitment and tacit knowledge underpin even the most formal scientific reasoning.

In clinical practice, every act of reasoning is shaped by what we notice, what we’ve experienced, and how we frame the situation. Mechanistic reasoning isn’t just about identifying what exists “out there”; it’s about making sense of it in a way that’s coherent, actionable, and integrated into the clinician’s judgment.

This leads to a tension between external validity and internal coherence: The mechanisms we invoke must both exist in reality and make sense to us as practitioners in context.

This is also where cognitive biases creep in. Our subjective interpretation of a particular instance can lead us to form flawed general beliefs—creating the illusion that we’ve discovered something objective. But it’s too simple to label the general as objective and the particular as subjective. In reality, both dynamics are in constant interplay. We navigate them every time we make a clinical judgment. Biases are the challenge across the board reasoning in and about the particular, inductively (or statistically) inferring generals from particulars, and in applying generals to particulars.

Why This Matters for the Next Lesson

This upcoming lesson isn’t just about modeling mechanisms. It’s about grappling with what counts as a mechanism, how we come to believe in one, and how causal explanations shape both our thinking and our actions. There are anecdotes about how mechanisms are necessary in practice because we can’t get all our decisions through experimental evidence (the parachute study phenomenon); and there are anecdotes about how holding out or relying on mechanisms leads to problems (such as waiting for germ theory to believe the empirical evidence (phenomenological observations) that hand washing reduced hospital infections. But what’s the balance - between objective and subjective, between generals and particulars - when reasoning about causal mechanisms in practice, and making decisions about or with causal mechanisms?

In other words, this isn’t just another page about methods—it’s about meaning. And that takes time to write well.

Thanks for your patience. More soon.

—Sean

Your reflective hiatus before your next essay brought to mind Gladwell’s book “Blink” and the potential dangers of “shortcut” assessments / thinking. There is, it seems to me, a bit of a chasm between Polayni’s tacit knowledge and Gladwell’s “intuitive” judgements. I’m looking forward to your upcoming post — take all the time you need.