We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

—T.S. Eliot, Little Gidding, Four Quartets

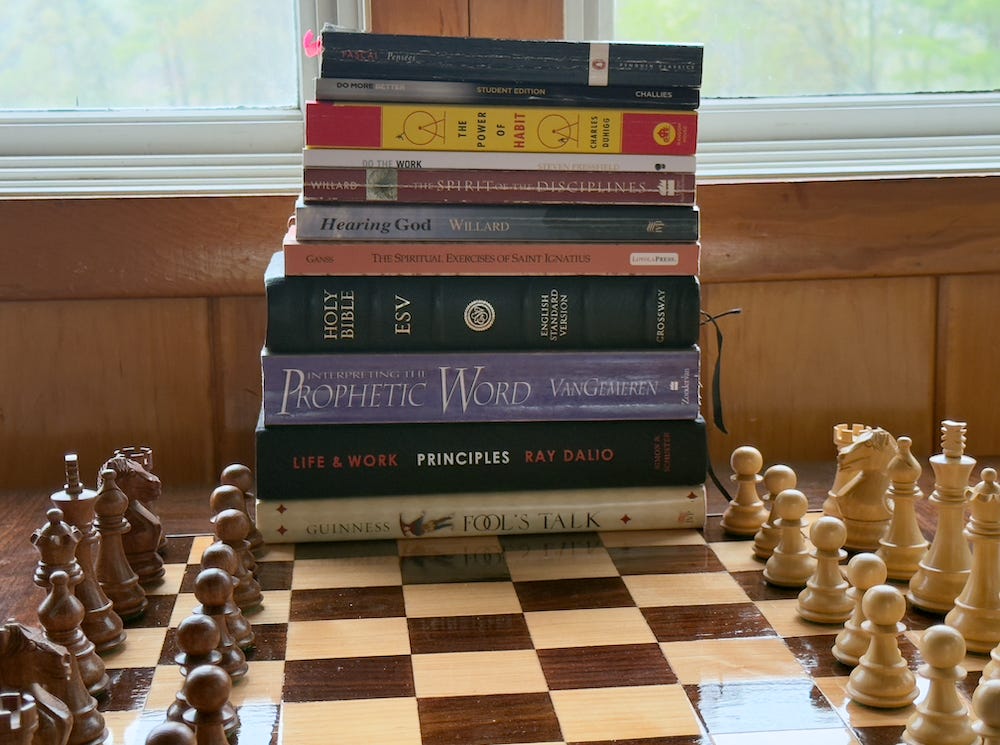

In my sun room sits a chess table I built. I recently set a stack of books on it. Texts that have shaped how I think, lead, reflect, and pray. This short stack is a visual anchor for my new season of leadership.

I’m returning to the role of Director in a program I founded ten years ago. It doesn’t feel like a promotion. It feels like a return. Not to power, but to presence. Not to prove something, but to serve more deeply from what I’ve lived. This is my third season of leadership.

A pastor, friend and mentor of mine, reminded me to:

“Recognize the seasons of your life and live accordingly.”

That advice resonates with me these days. I’m 55. My first season of leadership included energy and learning (38-43), and quite honestly was born from turmoil in a department of senior faculty, more experienced and senior than me, that struggled to get past their shared history. My second season included responsibility and refinement (45-51). I was building a program and bore the burden of making (and fulfilling) many promises of what we would accomplish with the new program. For a new PT program that rests firmly on achieving initial accreditation, and the promise that landed heavy on my shoulders was to the students that had trusted my promise. But this season is different. This season calls for anchoring. In faith, in formation, in fidelity to what matters most. I’ve come to believe that what I now have to offer isn’t fresh ambition, it’s depth, and hopefully, wisdom.

The Stack of Books on my Chessboard

The stack is not arranged by importance but by size for stability. The oldest book there is the Bible. Unopened some days, opened cautiously on others, but always there. It contains the foundation of values that helped shape what we expect and take for granted in the West - namely human dignity, moral equality before the law, care for the vulnerable, inner moral responsibility, freedom of will and moral agency, redemptive justice, forgiveness, the value of rest (sabbath), education and literacy. Whatever you think of it as a (collection of) book(s), it has been foundational for the Western world and it is filled with stories about leadership - good and bad.

Pensées by Pascal and Fool’s Talk by Os Guinness have a common themes despite the separation in time between the 17th and 21st centuries. I suppose that’s what makes these themes timeless. They remind me that meaning isn’t something I can manufacture. To “create my own truth” is a delusion, as Pascal warned, a diversion dressed as autonomy. Both books discuss the paradox of human nature, the limits of our reason, the need for an existential encounter, and our tendency to self-deception. And they both do so with an indirect style including paradox and irony that makes you think while appealing to conscience; they invoke disruption and draw people toward truth without coercion - a style associated with Socrates (Plato’s depiction), and Jesus (New Testament writers).

Nearby are books like Dallas Willard’s Hearing God and The Spirit of the Disciplines, and Ignatius’ Spiritual Exercises. They teach spiritual habits by forming them in a sort of “show don’t tell” way resonant of good writing on formation. They’re a reminder that you become who you are each day. Formation is a gradual process. A process for which today is necessary but not sufficient. Tomorrow is necessary, but also not sufficient. Two days from now is necessary, but not sufficient. In fact, every day is necessary, but not sufficient for becoming. Because, there’s another necessary day yet to come. What I do today is necessary, but not sufficient for the leader I hope to become.

Interpreting the Prophetic Word is academic. It’s the first book I read with my friend and mentor back in 2004 during his Wednesday at 6 am book study. The prophets tell fascinating stories. They weren’t just voices with predictions, they were leaders. They defined reality. They called people back to covenant, often at great personal cost. In this season of leadership, the calling to speak truthfully, to lead faithfully, to bear the weight of what others might prefer to ignore, feels resonant.

The Power of Habit and Principles are practical guides in this spiritually grounded stack. Prophets had habits. Good leaders have disciplines. Truth needs structure. Vision needs follow-through. Do More Better by Tim Challies and Do the Work by Steven Pressfield aren’t just about productivity; they’re about resistance. Resistance is something we face when we try to do anything meaningful. It’s the tendency to prefer to the lowest state of energy, to not do what should be done. Books on productivity, or on writing or on accomplishing anything meaningful, include systems and habits to push through resistance.

The chessboard holding the stack is not accidental. Leadership, like chess, is tactical, strategic, sacrificial and relational. There are goals to set, plans to be made, sacrifices along the way, and adjustments when necessary in response to the actions of another person and in view of the current action.

Formed by Pages and by People

Many of the books in the stack I’ve read alongside my friend. Over the past several years, we’ve met regularly for fellowship, accountability, and encouragement. What began as spiritual friendship has become a steadying force in my formation as a person and a leader.

His voice has influenced me for decades. Through sermons and book recommendations, study, conversation, and his writings on leadership and numerous other topics. His writings are distillations of a life marked by service, humility, and clarity. His words offer formation.

He writes,

“Leadership is not forged in crisis; it is revealed in crisis. It is forged in the discipline of faithful living day by day.”

That line threads its way through everything I’ve come to believe about this third season of leadership. The books may fill the stack, but that sentence anchors the posture I’m trying to bring to my work.

He has helped me see that the measure of a leader isn’t capacity but character. As he put it:

“A great leader is a person of integrity. Having an undivided heart, they seek to do what is right.”

That kind of integrity isn’t developed in an office. It’s cultivated in private, through time in reading and reflection, through small decisions when no one is watching, and through honest friendships that gently hold you to your better self.

Reading his sermon notes now, I can see how he lives what he teaches.

“What you are in private is what you are in public. You are not some compartmentalized product that can be turned on and off at will.”

That’s the kind of sobering truth a leader needs. Not to fear being found out, but to become whole enough that there’s nothing to hide.

So while the stack on the chess table is real, his voice woven into these years of friendship and formation keeps me asking the deeper question: Am I becoming the kind of person who can be trusted?

That’s the work now. Not gaining influence, but deepening trust. Not commanding outcomes, but walking in faith to support with those I’ve been called to serve.

What This Season Is and Isn’t

If I’m going to lead, I need to be full. Full of grace. Of time spent in silence, in reflection, in conversation that matters. The book stack reminds me. The chessboard reminds me. The people in my life remind me.

I may write more about this, or I may not. There’s a temptation to share every new insight, every piece of growth. But I want this season to first be rooted, and then be performative. I want to give more than I say. I want to mentor more than I post.

As my pastoral friend has written:

“Good leaders are always on the cutting edge of learning. They never stop asking good questions. They have the desire to view the whole picture.”

That’s the kind of leader I want to be in this third season: still learning, still asking questions, still seeing more of the whole picture. A leader shaped not by control, but by trust, integrity, and long-formed character. One who’s been formed slowly enough to be trusted. One who knows that the most important things don’t need to be tweeted. They need to be lived.

In closing, and with due respect to T.S. Eliot, I leave you with a poem as one whose life-long infirmary is being apoetic1.

As I arrive at the last of my seasons,

a place I’ve started before,

I will seek foundational reasons.

And arriving where I’ve started to explore,

I’ll come know the place for the first time.

“Apoetic” is not a standard English word, but it’s occasionally used informally or creatively to mean: Not poetic — lacking the qualities of poetry such as beauty, rhythm, emotion, or figurative language.

Hi Sean - good reminder for me that we are built on a foundation, and the building isn't done yet. I'm a year now into being in Todd's shoes (he's now Chair), and I thought I would be ready/ complete - I'm grounded but still needing to grow. A good but awkward (and at times painful) place to be.

I love this. It truly is who you build yourself to be when no one is looking that is what really matters.